Like your greens? One of our favorite opaque greens is the pigment PG17, chromium oxide green. It’s the color of money. Literally. Used in printing US currency, it has excellent lightfastness and archival stability. This rich willow green is reliable and a handy color mixer on the palette. And has an interesting backstory in the world of camouflage.

ORIGINS

Where does chromium oxide green come from? It can be found in nature as eskolaite, a rare green mineral. Named after the Finnish geologist Pentti Eskola, you can find it in rock formations and some types of meteorites. As science evolved in the 19th century, new synthetic pigments were discovered – often as by-products of chemical experiments in the lab. Colors previously found in nature as inorganic mineral pigments - like chromium green oxide – could be manufactured for mass use. In 1797, the element chromium was discovered by Louis Nicolas Vauquelin. Ten years later, he identified chromium green oxide, but it took some time to find a stable way to produce it. As early as 1809, the pigment was used as a colorant in porcelain making, but it had not yet been used as a paint. In 1838 the Parisian artist-chemist Antoine-Claude Pannetier established a stable way of mass production.

One of the first known uses in painting is a piece by J.M.W. Turner in 1812. The pigment appears more commonly from around 1845 and is seen in paintings by Moritz von Schwind, including his Mermaids Watering a Stag from about 1846.

PG17 vs PG18

In 1859, French chemist Charles-Ernest Guignet tinkered with the formulation and came up with a hydrated version. Chemically identical to chromium green oxide, he added an extra step ending up with two water molecules attached to the oxide of chromium. This turns the color from an opaque yellowish mid green to a darker, transparent, blue green. The pigment was named viridian, Guignet Green or emerald green, PG18. The color manufacturing process for viridian was patented and PG18 quickly became a brighter, flashier alternative. While the new pigment has overshadowed its duller cousin at some points in history, chromium green oxide has kept its place on the artist’s palette.

NOW YOU SEE ME, NOW YOU CAN'T

We go into the undergrowth to discover our next story on chromium green oxide. Up to WWII, the military used camouflage based on olive green colors to visually hide machinery and hardware. However, in wartime, infra-red photography was used for the first time. This was able to easily distinguish camouflage paint colors against natural vegetation.

Why? While the paint’s visible light spectrum was the same as the vegetation, it looked different on infra-red. Scientists experimented and discovered that chromium green oxide naturally mimics the optical infra-red reflectance of green plants – making it ideal for military camouflage paint and equipment. The new camouflage makes it harder to spot from the air and it continues to be an important pigment for military forces around the world. There’s now a special variety of the color made for military use called camouflage green.

IN PRACTICE

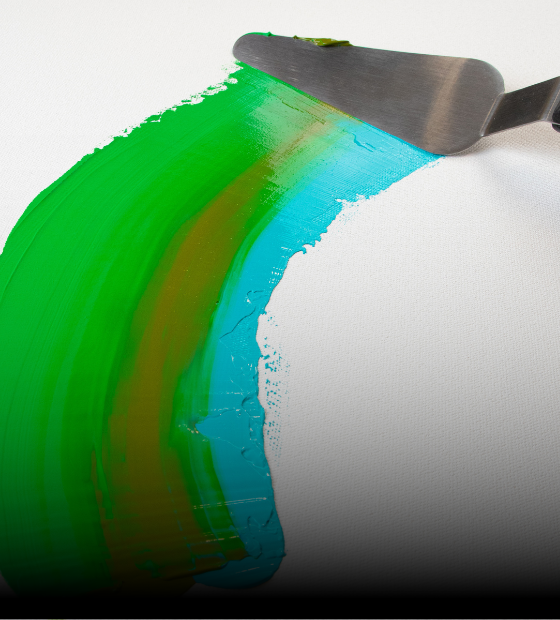

Chromium oxide green is a dense, opaque, slightly dull pigment. Loved for its mid-green tone, because it’s opaque, it’s liked for its ability to cover other colors and underdrawings. Useful for underpainting when painting portraits – try it and see – and for all kinds of foliage and botanicals. It’s the artist go-to for drab earthy colors. It gives a wide range of greens when mixed with other colors and has a high tinting strength. Add Raw Umber or Yellow Oxide to get earthy greens. When mixed with lots of Titanium White it makes a pale lemon color. Because it contains both blue violet and red reflectance, it has interesting mixing behavior with warm and cool colors. Just be careful not to over-use, as it can overpower many other colors.

Available in Professional Heavy Body, Soft Body and Spray Paint.

![LQX SOFT BODY ACRYLIC 166 CHROMIUM OXIDE GREEN [WEBSITE SWATCH]](http://uk.liquitex.com/cdn/shop/files/71838_9f4e8068-b965-4c4a-b02e-ed52e42826f6_375x375_crop_center.jpg?v=1709305832)

![LQX PRO MEDIUMS MATTE SUPER HEAVY GEL [WEBSITE SWATCH]](http://uk.liquitex.com/cdn/shop/files/72036_2fd2ed76-a56d-4f89-9ca7-1fa69ec8eda3_375x375_crop_center.jpg?v=1709304538)

![LQX SOFT BODY ACRYLIC 432 TITANIUM WHITE [WEBSITE SWATCH]](http://uk.liquitex.com/cdn/shop/files/71889_9cee19d1-f2b0-4e93-96ba-15a49cf02af8_375x375_crop_center.jpg?v=1736474413)

![LQX ACRYLIC MARKER SET 6X 2-4MM CLASSICS [CONTENTS] 887452001225](http://uk.liquitex.com/cdn/shop/files/68762_4855e6eb-82d5-4a11-a736-1f41ab15882e_375x375_crop_center.jpg?v=1709305272)